Field Notes

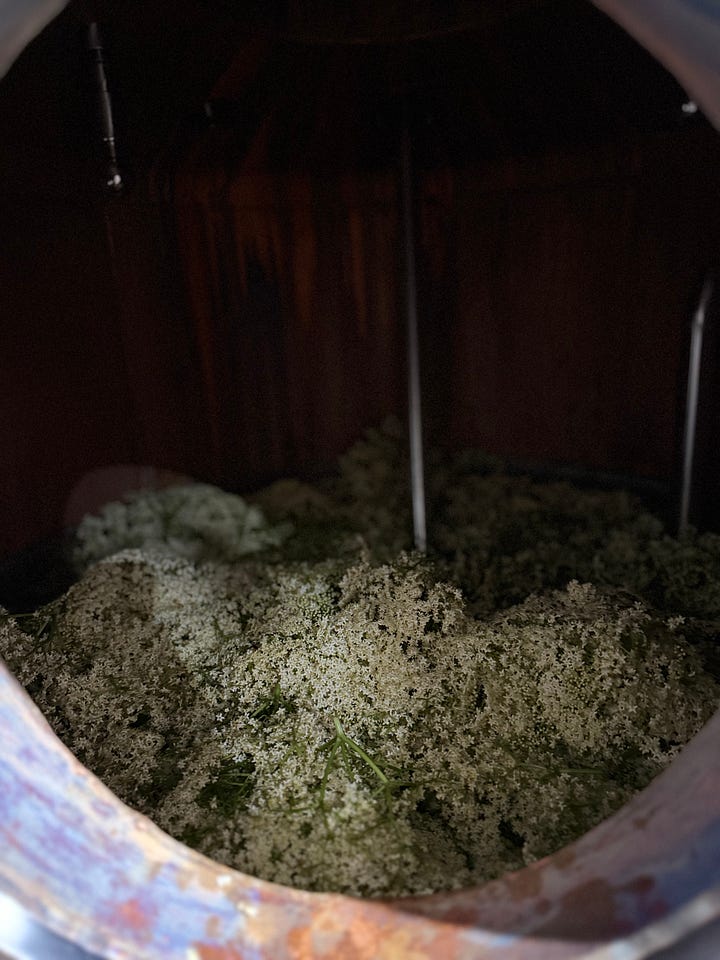

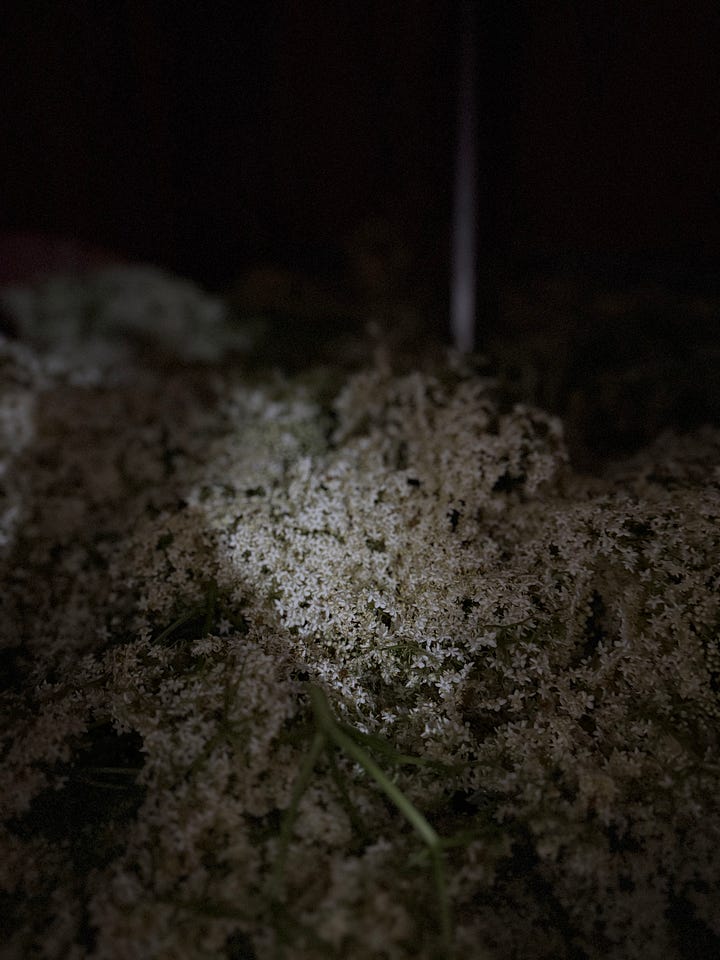

I’m back on the production floor—distilling freshly picked elderflower—coming off of a conference where I spoke about the natural world versus the synthetic one. For the first time, I found myself articulating the why of my work with ease—and I credit that to writing here. My head is usually a few steps behind my hands. Intuition leads. I used to design and plot and second-guess, but now I just move. Writing slows me down. It asks me to name what I’m doing and why.

In particular, it’s had me digging into the flavor matrices of ingredients that really hold my attention. Not just discovery or decision-making or process—but the research, too. Learning how to name with scientific specificity what I’m experiencing. That practice, more than anything, has clarified the difference between working with real ingredients and using artificial flavors and aromas.

Last Monday, I joined a panel with three iconic industry creators—Lance Winters (St. George), Lars Williams (Empirical), and Arielle Johnson (Flavorama), who moderated. The topic was Creative Distillation.

Of all that we discussed, I especially loved a moment Lance sparked when he brought up pandan leaf and tonka bean—how both contain notes of vanilla and coconut, but also so much more. Arielle and Lars expanded on the overlapping flavor compounds. They suggested: if you’re reaching for vanilla, maybe use pandan instead—its vanillin is wrapped in a chaos of other aromatics that lend dimension far beyond the base note. It’s something we’ve explored in The Dose before, but hearing them talk about it made me realize why I keep coming back to these ideas. It—natural aroma—is the part I can’t stop thinking about.

It’s like this: suppose your favorite color is blue. Now imagine living in a world where everything “blue” is just the one flat shade you’ve maybe only encountered when learning your primary colors. No indigo, no cerulean, no turquoise. That’s what it’s like to live surrounded by synthetic flavor and scent. We don’t notice what we’ve lost until we get a fleeting glimpse of nuance—and by then, perhaps we’ve forgotten how to even register it.

Flavor Compound of the Week: A Context

To make a rose in a lab, you start with a list:

Phenylethyl alcohol – soft, sweet floral

Citronellol – lemony-rose brightness

Geraniol – classic, slightly citrusy rose

Nerol – green and fresh

Linalool – floral with a hint of spice

Beta-damascenone – honeyed, rich, complex

Rose oxide – metallic-green nuance, for realism

Isoeugenol – clove warmth at the base

Blend those in the right proportions and you’ll get something that smells like a rose. Sort of. But it’s not a rose. It’s an idea of one. A stand-in.

A real rose is made of hundreds of aromatic compounds, many of which we haven’t fully mapped or named. Some are obvious and forward; others only matter in the way they lean against something else. And more than that—it changes. Hour by hour. Petal to petal. The way it smells in the sun versus the shade. The soil it grew in. The moment you touched it. Whether it’s blooming or beginning to wither. A rose is alive—and every moment you experience it is a different version of that life.

That difference—the one between the formula and the flower—might seem small. But it’s not. It’s the difference between an AI-generated image of a flower and a still life painted by someone who’s sat with it for hours. Who watched how the light changed it. Who noticed when it began to droop.

When we work with real ingredients—when we distill, infuse, macerate—we’re not reproducing a flavor. We’re capturing a moment. And in that moment is something ancient. For as long as we’ve been human, we’ve been drawn to scent and to flavor with no motive beyond joy. The rose doesn't feed us. It doesn't clothe us. It offers only itself—and that has always been enough.

Rituals + Objects

When I work with aromatic plants—harvesting, fermenting, distilling—what I’m really doing is paying attention. It’s not just production. It’s a form of respect. These ingredients arrive with a kind of urgency: fleeting, temperamental, full of character. And my job is to preserve them in a way that still feels alive.

The bottles we make at Matchbook are built for use, yes—but more than that, they’re built for natural indulgence. A small gesture, a glass raised, an intentional pour—each one a chance to experience the natural world as it once was, and still can be. You don’t need much. Just a little time. A little curiosity. A drink as a ritual, a moment to recalibrate towards nature.

When I think about others who have taken this kind of care, I think of Mandy Aftel—a perfumer and writer who has spent decades working with natural aromatics, studying their histories, and shaping them into perfumes that feel both ancient and startlingly present.

Her fragrances are made entirely from real materials—roots, resins, flowers, spices—and they evolve as you wear them, shifting with your skin, the hour, the air. She’s also written some of the most thoughtful books I’ve read on scent and ritual:

They’re not purely guides so much as they are frameworks for enjoying more, noticing more. For approaching scent—and the natural world at large—with a kind of quiet curiosity. If you’ve ever been stopped in your tracks by the smell of crushed herbs on your fingers, or found yourself leaning in to smell a bloom again, just to hold it a little longer—you already understand.

This is the rhythm I work in. These are the instincts I trust. And these bottles, in your hands, are meant to be part of that. Use them well.

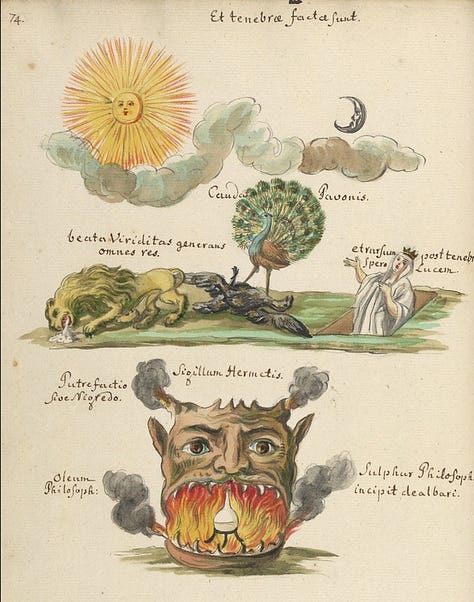

Lore / Artifacts

The alchemists believed you could liberate the essence of life from the parts destined to decay. That with the right raw material and the right process, you could create a tincture that enhanced beauty—or prolonged life. Their work was secretive, coded. But it gave us the alembic still, the foundational tool for distilling aromatics. And it gave us the idea that the essence of a flower or a fruit could be separated, preserved, transformed.

From alchemist to monk to perfumer to distiller—the thread runs unbroken. The monasteries made aqua vitae. The distillers made eau de vie. And here I am, still steeped in the same lore. Still enchanted by the fleeting power of the natural world. Still working to bottle what is already slipping away.

Things Worth Your Time

I created an aperitif from Jenny Lind, an endangered melon. By using the melon we paradoxically make it less endangered by getting a farm to plant the seeds, saving the seeds, and creating awareness and demand for this fruit. I’ve been chatting about it for awhile now and it’s finally available HERE!!!

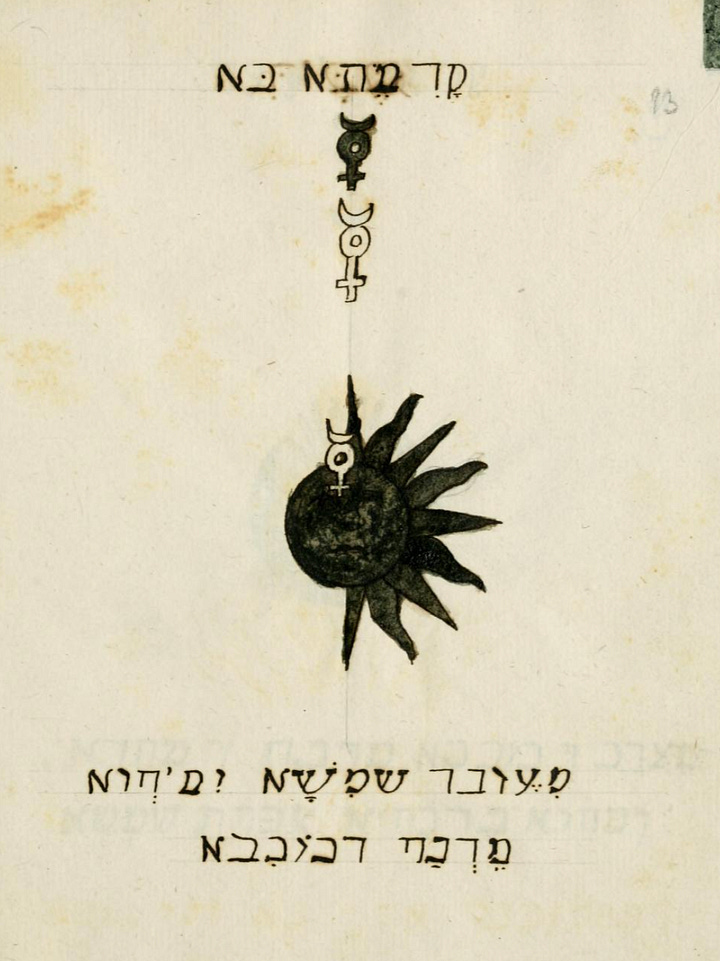

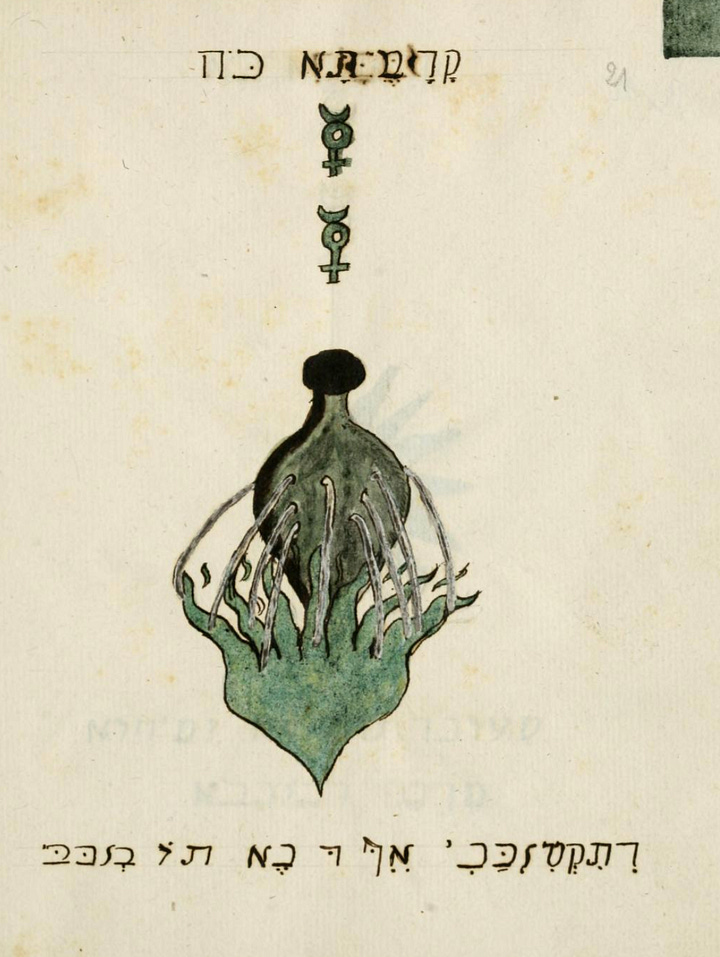

I really enjoyed looking through this digitally preserved copy of an alchemical manuscript from the Manly Palmer Hall collection. There were so many incredible symbols—a lot of references to the power of the sun, Venus, Mercury, the Moon, purification. The writing is encoded — utilizing Hebrew letters that likely function more as a cypher than a literal translation.

Manly Palmer Hall collection of alchemical manuscripts, 1500-1825

✨🙌✨

Great words on using real ingredients, capturing the moment.

Preaching this at my work.